Read in PDF version (including citations)

With a judgement dated 22nd November 2024, the Unified Patent Court (“UPC”) was called to decide on their very first FRAND dispute in Panasonic v. OPPO, a patent infringement case regarding Panasonic’s Standard Essential Patent (“SEP”). This decision is particularly relevant because it provides a deep analysis of the application of the required steps for SEP license negotiation described in the landmark decision Huawei v. ZTE of the European Court of Justice (“ECJ”).

I. Background:

The decision issued by the UPC concerns the European Patent EP 2 568 724 (“the patent in suit”), which Panasonic declared as essential for the 4G standard relating to a radio communication device and a radio communication method (4G telecommunication standards).

Panasonic filed parallel lawsuits against OPPO before the Mannheim local division of the UPC Manheim local division (hereinafter referred as to the “UPC”) as well as domestic courts, including German, UK, and Chinese courts.

Before the UPC, Panasonic brought infringement action against OPPO, seeking injunctive relief and determination of liability for damages and provisional damages, among others. Against it, OPPO argued that the assertion of the claim for injunctive relief and the other forward-looking claims under the patent are excluded because they are precluded by antitrust law (the “FRAND defense”).

Further, OPPO requested the declaration of invalidity of the patent in suit in its entirety with effect for the contracting states of the UPCA where the patent was validated. In addition, it filed a counterclaim for determination of a FRAND license fee for the territory of the European Union, Japan and the United States (the “FRAND counterclaim”).

In its decision, the UPC analyzed all the relevant steps set forth in the ECJ’s Huawei ZTE decision and ultimately ruled that OPPO infringed Panasonic’s SEPs and they are enforceable. As a result, OPPO is no longer allowed to sell its 4G-enabled products in Germany, France, Italy, Sweden, and the Netherlands. The court also ordered OPPO to pay provisional damages of €250.000 and dismissed the defendant’s counterclaims.

II. Court’s ruling on the FRAND Defense:

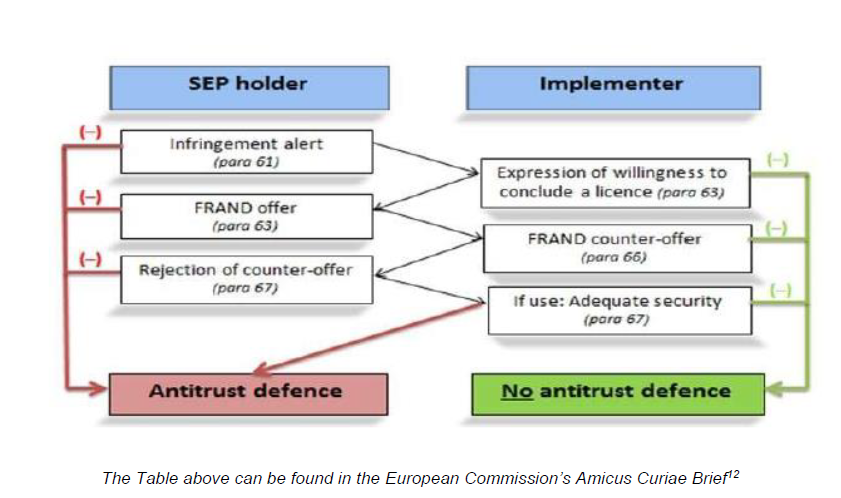

To arrive at this conclusion, the UPC thoroughly applied the Huawei v. ZTE framework to the case at hand to assess whether the FRAND defense was applicable. Under Huawei, the ECJ clarified that a SEP holder or an implementer who wishes to avoid or take advantage of a FRAND defense based on the SEP’s holder abuse of dominant position (art. 102 TFEU) must go through a mandatory sequence of negotiating steps. As a first step, the Huawei v. ZTE framework requires the SEP holder to submit an infringement notice to the implementer. The implementer upon receipt of such notice must express a willingness to conclude a license. After the implementer has rendered such declaration, the SEP holder must present the implementer with an offer on FRAND terms. Finally, the implementer shall diligently respond to the offer without delay, also by submitting a counteroffer on FRAND terms. If the patent user fails to comply with the obligations provided for in the Huawei ruling, the SEP holder would be eligible to seek injunction. However, if the SEP holder has not fulfilled its obligations under the negotiation program set by Huawei, the action for injunction will be regarded as an abuse of a dominant market position pursuant to Article 102 TFEU.

The UPC’s approach in this case somewhat differs from the recent European Commission’s (“EC”) opinion showed in the Amicus Curiae Brief submitted in the case HMD Global v. VoiceAge EVS, where the EC took a more rigorous and formalistic approach to the interpretation of Huawei v. ZTE. The EC reiterated that each step under the Huawei framework must be taken in a sequential order and should not be mixed up. Particularly, the EC emphasized that mixing steps 2 and 4 would compromise the balance of interests by the various Huawei steps and their precise sequencing, and such an approach would allow the court to grant an injunction without having to examine whether the SEP holder has submitted a license offer on FRAND terms.

Although the UPC agrees with the EC’s view in that the sequence of steps in the ECJ’s negotiation program under Huawei should not be mixed up in such a way that the examination of the SEP holder’s offer is pushed too far into the background, it put an emphasis on the interplay of the mutual obligations of both SEP holder and implementer in the negotiation program. The UPC states that both the SEP holder and the implementer must work towards the conclusion of a license agreement in good faith. Thus, according to the UPC, this requisite has various implications since just as the implementer cannot make a favorable offer without sufficient knowledge of any licensing conditions granted to third parties, the SEP holder cannot make a favorable offer if the implementer deliberately does not disclose the extent of its acts of use and economic conditions, such as the selling prices, depending on the progress of the negotiations.

Step 1: the submission of an infringement notice

The court started its reasoning from an analysis of the first step: the submission of an infringement notice from the SEP holder to the defendant. Under the Huawei v. ZTE framework, the SEP holder must first inform the patent user of the patent infringement of which he is accused before bringing an action for an injunction. In doing so, he must identify the SEP in question and indicate how it is alleged to have been infringed. It had already been established in the cited case law of national courts that the sending of claim charts is sufficient for these purposes in any case.

In interpreting this first step, the UPC disagrees with the view taken be the EC’s amicus curiae, which stated that a Huawei framework compliant notice of infringement should: “(i) express complains of patent infringement, (ii) name the patents concerned by number and (iii) state the nature and manner of the infringement in the letter itself.” Instead, the UPC ruled that “the ECJ judgement does not impose any strict formal requirements at this point, but leaves it up to the courts of the Member States to decide on a case-by-case basis”, and “[p]articularly in the case of an allegation of infringement of a large number of standard-relevant patents, a notice in the formalized form deemed necessary by the Commission may lead to confusion rather than the desired transparency.

In this case, the court found that the plaintiff sent the defendant a list of patents that it considers to be infringed for the 3G and 4G standards. The presentation explicitly designates the defendants’ 4G-capable products. The court further found that “the plaintiff submitted an updated list of patents deemed to have been infringed […]. This also contains a reference to the patent in suit.” In addition, the UPC pointed out that the plaintiff had sent the defendant a “claim chart concerning the Chinese family member of the patent family to which the present patent-in-suit also belongs, in addition to a large number of other claim charts requested by the defendants[.]”

Therefore, the UPC decided that in the instant case the first requirement was met and that the notice was “sufficient.”

The UPC stated about the defendants’ objection to the sufficiency of the notice of infringement, “objections that this was not sufficient for the comprehensibility of the infringement allegation were raised by the defendants for the first time at the oral hearing. This is late. […] If there had been a need for clarification here, the defendants, as a cooperative license seeker, could and should have asked the plaintiff.”

Step 2: declaration of the willingness to take a license

Then, the UPC moved onto the second step of the analysis: the willingness to license of the defendant. This second step, according to the European Commission’s amicus curiae, should be assessed solely on the basis of the content and circumstances of the declaration, not on the basis of subsequent conduct during any negotiations, and this step must not be mixed up with the subsequent steps, the offer of the SEP holder and the counteroffer of the patent user. Although the UPC agreed with the EC’s view in that the initial declaration of willingness to take a license marks the start of further negotiations, it went on to state that “it has not yet been clarified to what extent the further conduct during the negotiations is to be included in the assessment.” The court further stated that, “the seriousness of the initial declaration of fundamental willingness to take a license, understood in this narrower sense, is to be assessed from the accompanying immediate circumstances”, but “it does not follow from this that the further conduct of both parties during the subsequent negotiations should be ignored in the examination.”

In the present case, the UPC found the second step has been satisfied because “[i]n their email […] the defendants made a sufficient declaration and named a specific contact person for further discussions” and as such “the defendant’s statements at the receipt of the negotiations appear sufficient to be regarded as a sufficiently serious prelude to further negotiations.”

Step 3: an offer to license on FRAND terms

Later, the court’s attention shifted to the examination of the third step: an offer to license on FRAND terms from the SEP holder. The UPC found that the SEP holder, when submitting its offer, must not only state the mere mathematical factors used to calculate the license fee. Rather, it is also obliged to explain, in the manner possible for it according to the state of the negotiations, why it believes its offer as FRAND-compliant. The SEP holder has better knowledge of its licensing practice and should communicate this to the patent user so that the latter can react in good faith. However, the UPC further stated that the extent of the explanations depends on the respective stage of negotiations between the parties. It is therefore not necessary in every case to disclose the names and terms of the third-party license agreements immediately for the purpose of plausibility.

Based on the above, for the present case, the UPC stated that, based on the plaintiff’s presentation on the economic cornerstones of its offer and the reason on why it considers its offer is reasonable, the plaintiff had already clearly explained its demands at an early stage and sufficiently demonstrated the plausibility for the further negotiations as to why it believes its offer is FRAND-compliant. Then, the UPC stated that if the defendants, as cooperating license seekers, still had questions, e.g. regarding the non-discriminatory nature of the offer, they should have asked them immediately or shortly thereafter.

Although the defendants objected that a written contractual offer is required to be regarded as an initial offer, the UPC did not uphold such a view. The UPC stated that “this does not require a written contractual offer that is differentiated in all secondary points and ready to be signed,” but that “it is sufficient if the SEP holder’s offer allows the patent user to recognize the essential economic framework conditions of a proposed license agreement.” On this point, the UPC pointed out that the defendants would have been required to raise objections, submit counter-proposals or raise economic issues to be clarified, raising such questions by means of a private expert opinion only before the court cannot replace this obligation to cooperate.

The UPC found that the plaintiff at this point did not have to provide more information, including license agreements with third parties used for comparison purposes, and ultimately deemed the plaintiff’s last submitted offer as FRAND-compliant.

On the other hand, with respect to the implementer’s side, the UPC pointed out that depending on the stage reached in the specific negotiations, a license seeker negotiating in good faith can nevertheless be expected to make its own sales data available for certain periods of time in order to check the plausibility of its own objections to the figures used by the other party. Particularly, according to the court, the patent user must provide information after the next step, the rejection of its counteroffer, in a form that enables the SEP holder to assess whether the security to be provided is sufficient and, in particular, covers an insolvency risk. The court found that the defendants did not provide such information at any time.

Step 4: a counteroffer by the defendant

The fourth step: the counteroffer by the defendant was then analyzed by the court, however we cannot delve into their evaluations as their reasoning was redacted from the decision. What we know is that the court decided that OPPO’s counteroffer was not FRAND-compliant.

In this regard, the UPC stated that a license seeker in good faith in OPPO’s position should be expected to share sales information with Panasonic at this stage of the negotiations, since the ECJ requires certain information to be rendered to the other party for the calculation of the security deposit. Further, the UPC also decided that the security deposit was insufficient. Having said that, while the plaintiff fulfilled its obligations in accordance with Huawei framework, the defendant did not fulfill its obligations, and the UPC denied the defendant’s FRAND defense based on EU antitrust law, whereby it ultimately affirmed the plaintiff’s claim for an injunction.

III. Court’s ruling on the FRAND counterclaim:

In addition, with respect to the defendant’s counterclaim for determination of a FRAND license fee for the EPC, Japan and the USA territory, the UPC ruled that “[t]he UPC has jurisdiction for the counterclaim filed by the defendants together with the statement of defense, which is aimed at determining a FRAND license. Jurisdiction follows from Art. 32(1)(a) UPCA. Accordingly, the court has exclusive jurisdiction over actions for actual or threatened infringement of patents and related counterclaims, including counterclaims relating to licenses. This includes not only disputes relating to existing licenses to a patent, but also lawsuits aimed at the conclusion of a license.” While the FRAND counterclaim was found admissible, it was dismissed as unfounded based on OPPO’s “unwillingness”. In particular, the main claim, which consisted in the issuance of an order against Panasonic to “accept the license agreement offer from Oppo”, was rejected because the “the lump sum license fee submitted by the defendants in the offer to conclude the contract is not FRAND-compliant” since it was calculated solely “on the basis of the IDC data disputed by the plaintiff” rather than Oppo’s acts of use. Further, with respect to OPPO’s request for the UPC to determine the license fee within the limited territories of Europe, the United States, and Japan, it ruled that while “both parties ultimately agree in their arguments that only a comprehensive dispute resolution through a global FRAND rate determination is in line with customary practice” , “the defendants have also not put forward any arguments that could justify a partial determination of the license rate only for certain global regions”.

IV. Conclusions and implications for future cases:

This case was highly waited for the UPC’s interpretation of the ECJ’s Huawei judgement, thereby the UPC issued the first ever injunction based on the infringement of SEP. As thoroughly described in this article, the UPC took interpretations of the Huawei framework that are somewhat deviating from the EC’s position described in its amicus curiae brief.

It is also worth noting that the UPC addressed the issue as to whether the UPC had jurisdiction over FRAND counterclaims and the setting of a FRAND rate. In fact, there were debates on this point. In the absence of any provisions in the Unified Patent Court Agreement on the jurisdiction of the court over FRAND matters, this declaration of jurisdiction of the UPC is an important highlight. Unfortunately, not much is said about the possibility of setting the terms of FRAND royalty rates, which is currently still uncertain. Nevertheless, the court did not completely deny the possibility to determine FRAND rates, since it confirmed it had jurisdiction on the topic, and the question of whether UPC will use this chance is still to be answered.